In February 1969, Tony, BBC producer Ray Sutcliffe and I arrived in the Falkland Islands on the RMS Darwin from Montevideo, Uruguay. Tony and I were there to film the people and wildlife for the BBC’s World About Us, and Ray needed some footage of the Great Britain for BBC Chronicle.

The old ship lay in the small Sparrow Cove a boat ride from Stanley. Our first sightings in the barren landscape were of a broken hulk, dominated by three huge masts, with a big crack down the starboard side, holes at the base of the hull, rotten decking and rusty girders below. I must admit, while having absolutely no experience of salvaging shipwrecks, this looked a very daunting task. We knew that a straightforward tow back to the UK had been ruled out, so some other method would have to be found. With film in the can, Ray left for London, while we continued filming in the Islands and then returned to Peru.

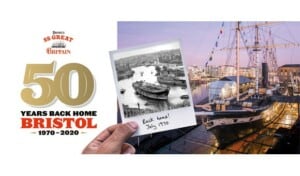

Tony and Ray capture the scene before salvage work begins.

Almost a year passed before news came through that money had been raised and experts believed the salvage to be possible. We had little time to prepare before making our way to Montevideo to meet Ray, and catch the monthly sailing of the Darwin.

In Stanley we lodged with the Summers family in their cosy Woodbine Cottage overlooking the harbour, and each day soon after dawn we motored out to the ship on the Royal Marines’ workboat, the Marauder. Mostly it was cold, and windy with choppy waves. Getting on board the Great Britain was up a rope ladder placed over the starboard crack, and then negotiating the rusty foot-wide girders with nothing between us and the dark waters deep below in the bottom of the hull. All the while carrying our equipment. This was, perhaps, not the best timing to be pregnant!

Scuttling holes, knocked through the ship’s hull in 1937, allowed every high tide to flood the interior.

Our gear included 16mm Bolex cameras, using 400-foot spools which had to be changed at speed when things were happening. Also several still cameras as I was covering the story for the Observer Magazine, tripods, and over 15,000 feet of negative film.

A salvage tug, the Varius II, arrived in the cove towing from West Africa an enormous submersible pontoon, the Mulus III. The aim was to make the Great Britain sound, safe and secure on the pontoon and tow her back to the UK. The Anglo-German salvage teams worked together, first making the upper deck safe, and next taking down the 32-metre long spar on the main mast. Once this was accomplished Tony insisted, rather against Ray’s better judgement, on climbing the nearly 30-metre high main mast to get a last shot looking down on the Great Britain’s main deck.

The mizzen was the first mast to come down. While Tony moved around using a handheld camera, I was despatched ashore to get a different angle, and sat in misty rain for about five hours before unfortunately the mast crashed through a deck house. But I did get the shot.

A mast has just been lowered safely: Marion’s photographs record the risk and exhilaration of the salvage.

Each day something new and different happened. As the only woman around, if necessary, I had to avail myself of the original Victorian loo holes in the bow. There was little shelter from the bleak weather and we always looked forward to returning to the warmth of Woodbine Cottage where Aub Summers cooked a delicious supper of lamb or goose on a peat stove, after which we collapsed into bed. We had absolutely no energy to visit one of the many pubs in Stanley.

The Falkland Islanders often came in their small boats to catch up on progress, which on one particular night proved very fortuitous. The Great Britain had floated for the first time – her holes patched, water pumped out – when a storm blew up and suddenly the lines holding her to the shore threatened to break. Caught by the storm, the islanders with their boats stayed overnight and held the ship steady. For hours I lost Tony and Ray as they also set off in a small boat to help but eventually all of us finished up sleeping in a shepherd’s hut on the shore until the wind calmed down.

We made daily recordings of each day’s work with members of the crew. The recordings went out on the Islands’ radio station so that islanders living far from Stanley could be kept in touch with what was going on.

Tony (left) and Captain Malcolm MacLeod collect old mattresses for patching the cracked hull.

It took two attempts to get the ship onto the pontoon. I remember sitting, freezing, at the top of Snake Road in Stanley watching the Varius and two smaller tugs carefully towing the Great Britain on the pontoon through the Narrows at the entrance to the harbour, in the middle of a snowstorm with bad visibility and a tremendous wind. It was an amazing sight and extraordinary achievement.

It was also a moment when I felt incredibly privileged to be part of such an historic event. Filming had at times been challenging and exhausting but there was great camaraderie on board and a huge sense of elation when eventually the flotilla arrived safely in Stanley. For Tony and I, it was certainly one of the most memorable projects we were involved in capturing during our fifty year association with South America.

Preparations then went ahead for the return to the UK: speeches from the Governor, gifts of original SS Great Britain artefacts from Falkland Islanders including a bath and the ‘captain’s table’, and first day covers stamped on board. On the morning of 24 April 1970, watched by a crowd of sightseers, the Great Britain left the Falklands, with Tony and Ray on board.

SS Great Britain sets out on Mullus III from Sparrow Cove to Stanley for her send-off from Falkland Islanders who had sheltered her for 84 years.

I was not allowed on the tow but was lucky enough to be offered room in the Royal Navy hovercraft, from which Sarah Swanick (the Governor’s PA) and I were able to give the Great Britain a final send-off into the South Atlantic.

A few days later I left on the Darwin, overtook the Great Britain sometime in the middle of a night and arrived ahead to greet her into Montevideo. We then flew back to the UK and the Great Britain began its lengthy tow back to Bristol.