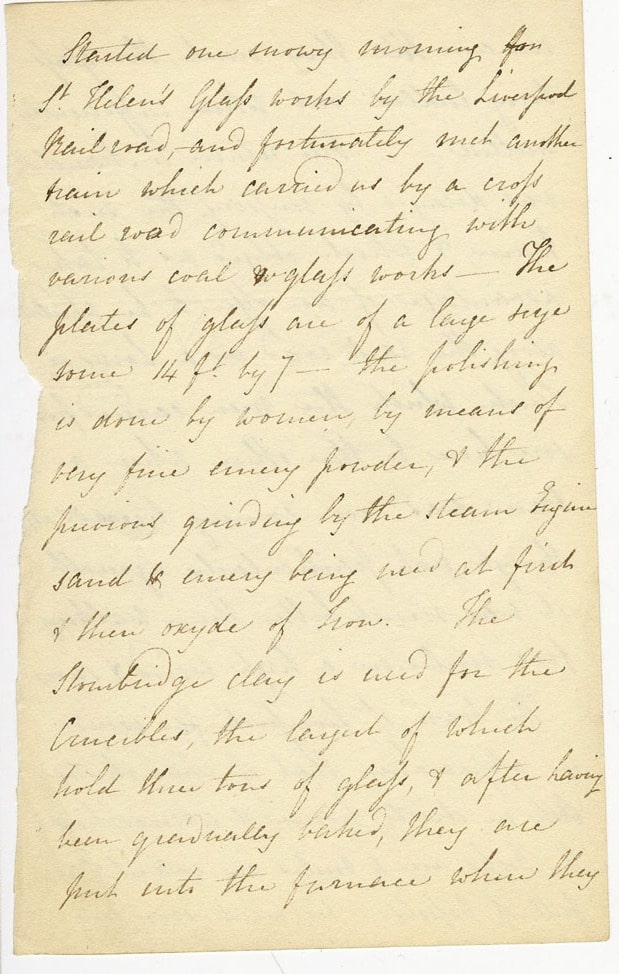

- This is Sophia Hawes’s handwritten account of a visit she made to Manchester and Liverpool sometime between 1838 and 1839.

- She travelled there by train from London, a journey she described as being as comfortable as “a ride of a few hours on the pavement of London when the road is on level ground”. Once in Manchester, Sophia explored the city’s iron foundries, cotton mills, and silk mills to look at their machinery and manufacturing processes. While in Liverpool, she visited the city’s dockyards.

- The account is several pages long and is likely to have originally been in her diary or notebook. However, it was torn out at an unknown later date, and sadly we only have some of the pages, meaning parts of the account of the visit are missing.

- Sophia’s father, Marc Brunel, and brother, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, were both engineers, but as a woman in Victorian Britain, this career was not an option for her. Despite this, Sophia’s journal shows she had a very detailed knowledge, interest and understanding of engineering.

The Story

Visiting Manchester and Liverpool

The 212-mile train journey from London to Manchester, took Sophia eleven hours; during that time, she wrote about the challenges faced by railway engineers ‘when the country is hilly’. She notes the need for embankments and tunnels plus highlights the advantages of planting vegetation for drainage. Her insights show her excellent understanding of the engineering processes and challenges behind designing and building railways.

In Manchester, Sophia visited silk and cotton mills, warehouses, and iron foundries. She describes in detail the processes that turn the cocoon of the silkworm and raw cotton into the finished fabrics. Her comments pay special attention to the machinery that she sees in action. In one cotton mill she recognises machines created by her father Marc Brunel and writes “here were 36 of Papa’s machines for weaving cotton”.

In Liverpool, Sophia visited the dockyards, Town Hall and the not-quite-finished Custom House. It appears she preferred Liverpool to Manchester, writing ‘Liverpool far exceeds in appearance that of Manchester […] in streets, houses and atmosphere.’ She also visited the glass works at St Helens, but her train back to Manchester was delayed, which resulted in her taking advantage ‘of an offer to be wheeled along the railroad in a long truck which the men carried from one line to the other when a train was seen coming’!