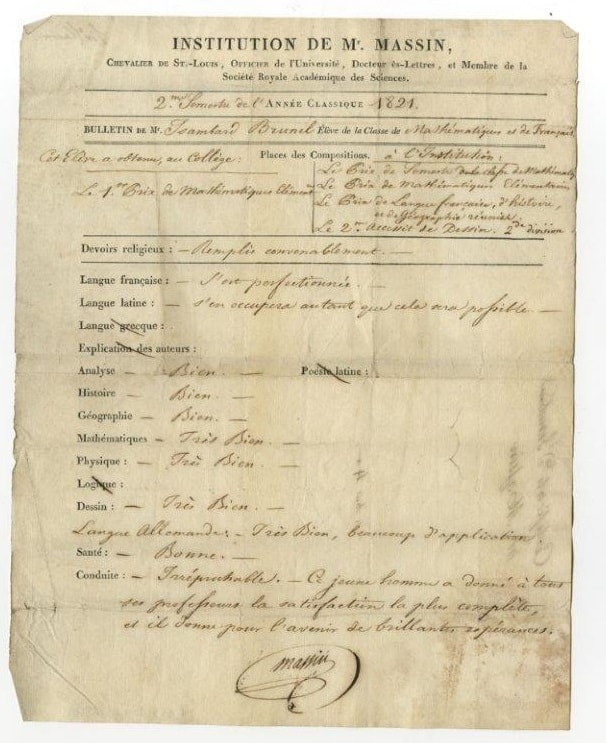

- This is Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s school report from the Institution De M. Massin in Paris; the report is dated 1821, when Brunel was 15. The report is written in French by Mr Massin and highlights some of Brunel’s talents.

- The report lists the awards he received at the school, including 3 separate maths prizes, and states his progress in a range of subjects. It describes Brunel as “very good” at maths and drawing, while his ability in both history and geography is labelled as “good”.

- Brunel knew several languages. His teacher writes that he is “very good” at German, his French is “improving” but when it comes to Latin the report says only that “He will deal with it as much as it will be possible”.

- The report also mentions his health, which is described as “good”, and his behaviour: “beyond reproach – This young man gave to all his teachers the fullest satisfaction”.

- The final line offers an insight into Brunel’s potential as Mr Massin writes “he provides brilliant expectations for the future.”

The Story

Brunel’s education

From a young age Brunel’s potential was clear. Whilst he was at his first boarding school, Dr Morell’s in Hove, Brunel started the habit of drawing and measuring in detail, any buildings he saw that interested him. In his spare time, Brunel carried out a survey of the buildings in the town; whilst doing this he predicted that some houses, which were in the process of being built, would collapse. Strong winds the next day caused the buildings to fall and proved Brunel to be correct allowing him to win a bet against his school friends!

When he was 14, Brunel was sent to school in France by his father, so he could gain a technical education. As well as the Institution De M. Massin, Brunel also attended Caen Collage in Normandy and the Henri-Quatre Lycée in Paris; both schools were famous for their teaching of engineering and maths.

Marc Brunel wanted his son to attend the well-known engineering school Ecole Polytechnique; however, as Isambard was born outside of France, he was not eligible to attend. Instead, Brunel became an apprentice to Louis Breguet who was a famous maker of watches, chronometers, and scientific instruments. Working for Breguet allowed Brunel to develop his practical skills.

Brunel returned to Britain aged 16 and started work in his father’s office as an engineer, designing bridges. By the age of only 20 he was the Chief Engineer of his father’s Thames Tunnel project.