The Object

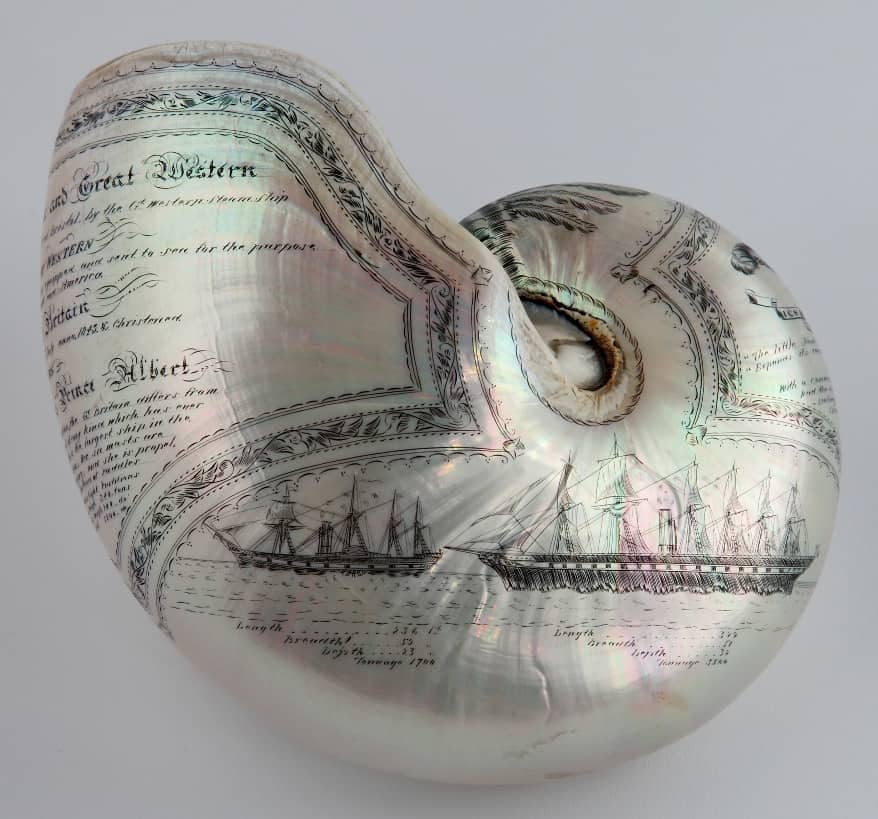

- This engraved nautilus shell shows the paddle steamer PS Great Western and the SS Great Britain – the SS Great Britain is the larger ship. It also has descriptions of the launches of both ships, and details of how they were built.

- The shell was engraved by Charles H. Wood. He worked in Liverpool in the mid-nineteenth century, engraving many nautilus and turban shells. He said that he only needed a small penknife to create his beautiful designs.

- An exact copy of this shell was given to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Charles H. Wood said that the queen had accepted several pieces of his work.

- In the 1840s, people were very interested in big projects like the building of the SS Great Britain. Hundreds of souvenirs were created and sold, and engraved shells, often from various ocean living molluscs, were one of the most popular types of souvenir.

We’d like to thank Lizzy for the work she did towards this collection story as part of her university placement.

The Story

Souvenirs from the sea

Souvenirs of large engineering projects, such as the SS Great Britain were popular in the Victorian era. As travelling on holiday became more popular, people also wanted souvenirs of the places they visited. Souvenir coins, mugs, peepshows, engraved shells and other objects were all produced and sold.

Charles H. Wood produced highly decorated engraved shells, many showing projects such as the SS Great Britain and SS Great Eastern, that were sold as souvenirs. His style of engraving, using a penknife, is very similar to the process known as scrimshaw, a craft that began in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, aboard whaling ships.

With lots of whale teeth and bones to use, creating scrimshaw was part of life on board for the crew of the whaling ships. A whale’s tooth or bone would be scraped and sanded to give it a smooth surface, then a piece of paper with a drawing could be placed over it. A sailor would use a needle to prick the outline of the drawing onto the tooth or bone, then remove the paper and “connect the dots”. Some sailors were able to carve their drawings freehand. Once the lines were finished, they could be filled in with lamp black (a traditional paint made from soot and water) or coloured dyes.

Lots of different things were created in this way. Some of them were only meant to look interesting, such as a decorated sperm whale’s tooth. Scrimshaw could also be used to decorate more useful things such as a napkin ring or a corset busk (something to stiffen a corset and give the wearer a tiny waist). Sailors often gave scrimshaw to their loved ones back at home, as a souvenir of their voyage.

Continue The Story

The Great Exhibition

A large nautilus shell engraved by Charles H. Wood was one of about 100,000 objects displayed at the Great Exhibition in 1851. The idea for this exhibition was developed by Prince Albert, who wanted to display the treasures and technologies of the world (especially Britain, and the then British Empire) for all to see.

The exhibition took place within a “Crystal Palace”, designed by Joseph Paxton. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was a member of the building committee and came up with a design himself. But he ended up agreeing that Paxton’s design for a building made of glass and iron was better. In the middle of the building there was a huge fountain standing over 8 meters high, made of four tons of pink glass.

Inside the Crystal Palace, over half of the space was taken up with exhibitions from Britain and countries that at the time were part of the British Empire; of the other countries that took part, France brought the most exhibits, including examples of furniture, tapestries and silks. Some other highlights of the exhibition were huge vases from Russia, twice the height of a person; an Indian throne made of carved ivory; a printing machine that could create 5,000 copies of the Illustrated London News in an hour; “tangible ink” for blind people, which created raised letters on paper that could be read like modern braille; and giant railway locomotives.

The exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria on the 1 May 1851, with an admission price of £3 for gentlemen and £2 for ladies. This was reduced to one shilling for everyone after a few weeks, and people travelled from across the country to visit. The exhibition was seen as very educational, children visited on school trips and many factory workers and other working-class people were sent by their employers. While there, people were able to buy souvenirs such as medals and peepshows to remember their visit. Over six million people had visited by the time the exhibition closed in October 1851, about a third of the British population at the time.